I still have more Caribbean mermaids in the TBR pile. But a particular element from The Mermaid of Black Conch resonates with a well-known film. That’s what I’d like to talk about this week.

Guillermo del Toro’s The Shape of Water won an Academy Award for Best Picture in 2018. I avoided it because I am not the intended audience for films full of Deep Thoughts That Are Good For You, which was the impression I had from the reviews and commentaries. I also bounced off the disability narrative, for reasons partially summed up by Elsa Sjunneson-Henry in an article on this site.

Monique Roffey’s book features a deaf character who manages to open communications with the mermaid. She had language in her human life, but a millennium as a sea creature took away her memory of it. Reggie’s American Sign Language helps her find her way back to spoken language.

For anyone who has grown up in or around the Deaf community in the United States, especially if they’re old enough to remember the Sixties and Seventies, this narrative choice triggers some deep feelings. It was an ongoing battle to get ASL accepted as a language. Language, we were told, was spoken—i.e., for hearing people only. ASL was inferior, a make-do; as the National Science Foundation puts it, “a pantomime, a poor substitute for spoken speech.”

In the 1960s, the linguist William Stokoe blew up this perception. ASL, he wrote, is a language in the full sense. It has grammar, it has syntax. It’s its own, autonomous, fully developed, naturally evolving linguistic phenomenon. It’s a visual language. It uses gestures, facial expressions, and body language, rather than spoken sounds.

This was huge, and it took decades to penetrate the general culture, let alone academia. Roffey’s Reggie, in 1976, is on the cutting edge—he’s just old enough to know ASL as a full-fledged language. Elisa in The Shape of Water, in 1962, is living right at the time when Stokoe was publishing his work.

That’s the background I brought to the film. I had ignored it assiduously enough to not realize that Elisa is not deaf. She’s mute; her vocal cords were apparently severed in infancy, represented by a trio of scars on her neck. She can hear perfectly well, she just can’t speak.

Her version of Sign is not genuine ASL. She uses bits and pieces of it, well enough that her best friend Giles and her coworker Zelda can serve as interpreters. In a way she represents ASL as it was perceived at the time. It’s not a full-blown language; it’s how she makes do.

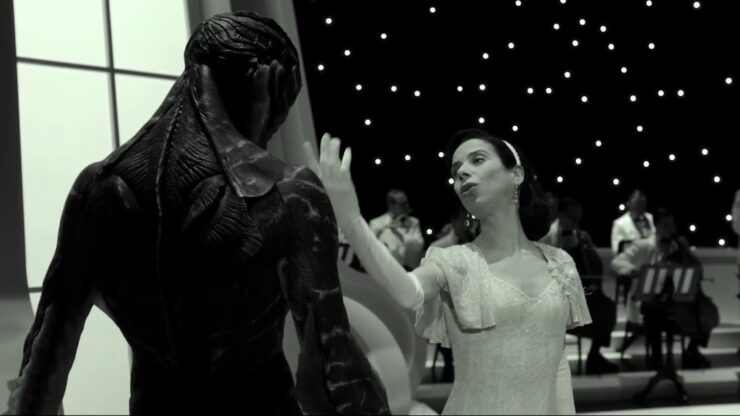

It’s also, as with Reggie and the mermaid, how she opens communications with the Amphibian Man. None of the abled humans in the secret government facility has figured out that the aquatic humanoid from the Amazon is sentient, still less tried to communicate with him. Elisa catches on immediately, is totally unafraid of him despite seeing the serious damage he can do to a human who gets in his face, and quickly falls in love with him.

I wonder if there’s some telepathy going on there. (I have not read the novel that was written in parallel with the film. If you have, do let me know if coauthor Daniel Kraus has anything to say about this.) There certainly is a bond, and it rapidly evolves into a sexual one.

Mermaid films in general don’t go into detail about the sex part. Del Toro not only goes there, he does it early and often. We know exactly what Elisa and the Amphibian Man do, and Elisa lets Zelda know, in a concise set of gestures, how one particular element works.

It might be argued that Amphibian Man is not technically a merman. He’s more of a cryptid, the direct descendant of the Creature from the Black Lagoon. But then again, he reads as a relative of Poul Anderson’s mermen. He’s less humanlike, but he’s two-legged, his feet and hands are webbed, and his face though alien has distinctly humanoid features.

We know he’s sexually compatible with a human woman. He was worshipped as a god in his native habitat, we’re told, which makes me wonder if he’s had human lovers before Elisa. He has certain powers that echo the powers of the mermaid in other works, notably Ten-Cent Daisy: the power to heal and even, apparently, to revive the dead.

The scientists who study him in captivity discover that, like Anderson’s mermen, he has two sets of breathing apparatus, one for air and one for water. He can live out of water for a while, but he has to go back to it within hours or days, or he dies. Though what happens after that seems to reflect on his godhood.

Or maybe he’s an organism that goes dormant in adverse conditions, and revives when the water comes back. The film doesn’t explain. In that respect, it takes us into fairytale territory. Just go with it, it seems to say.

Fairytale (lack of) logic may also be why this denizen of the Amazon River can’t survive without salt. Just like Madison in Splash, he spends considerably quality time in a bathtub, well pickled in kitchen salt. He has no tail to unfurl, but he does have some nice glowy blue effects when he’s wielding his superpower.

Spoilers for the film follow. Skip if you haven’t seen it and would like to be surprised.

Amphibian Man is not the only water creature in the film. I had suspicions as soon as I saw Elisa’s neck scars. Sure enough, at the very end, after they’ve both died and he’s come back to life, cue the glowy blue effects—and her scars open into functioning gills. And so they swim off together into the wet blue yonder.

Is this the healing superpower in overdrive? Does he do it to keep her with him once he’s resurrected her? Or is she a cryptid herself? Is she an aquatic creature whose gills atrophy while she lives on land, and when he heals her, he restores her to her true self?

There are hints throughout the film. She has ongoing underwater dreams. She’s strongly drawn to Amphibian Man, and she keeps gravitating toward water, whether it’s the bathtub or rain or the ocean. The actress, Sally Hawkins, has a distinctive look, with a wide, almost fishlike mouth. She looks like a water creature; it seems natural for her to end as she does.

I wonder if, in the future beyond the film’s ending, she transforms further; if she develops webbed hands and feet, the better to swim with her lover. Does she keep the ability to breathe air? Or is she now completely aquatic? Is it possible she’s the larval form and Amphibian Man is the adult?

After all, it’s not exactly clear if he’s a one and only. She could well be another of his kind.

Or not. Only the filmmaker knows for sure.